Umlaut Big Band

Artwork von A. R. Penck

Photo: Dagmar Gebers / FMP-Publishing

Outside Traditions

“The idea behind the concept of the ‘outsides’ is that music is not just the notes, the formal kind of construction, the harmony, the melody, the rhythm. But there is something beyond and in excess of those elements themselves that they express. And those things come from particular traditions that have been developing over many years. If you think about the music as the insides, what of the outsides is present inside? That’s the one sense – the cultural, historic, or political context that produces certain forms of music. And then, the out-side also is about the idea of playing out, you know, more avant-garde. Music that is pushing beyond a certain kind of formal limitation. A pursuit of freedom in the music, I guess, and a pursuit of freedom outside of the music as well.”

— Asher Gamedze

1

DecolonialLegacies

Radicalism and Spirituality in South African and US Jazz

In many respects the history of jazz in the USA and South Africa is entwined with the experiences of discrimination and resistance as well as with the cultural practices, social utopias and collective self-assertion of marginalised population groups. In a conversation about how music and society interrelate with each other, Asher Gamedze offers insights into his work as a musician and historian and how certain forms of musical expression originate aesthetically in the experience of and struggle against racism and oppression. A series of graphic scores provides a taster for the premiere of the fourth chapter of “Coin Coin” – Matana Roberts’s exhaustive exploration of the American past which she examines with the help of her own family history. And in a video interview with Peter Margasak, alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins talks about his musical beginnings at church, his latest album, and the relevance and irrelevance of terms such as spiritual jazz and Black radicalism with regard to the current renaissance and popularisation of pertinent aesthetic traditions in the USA.

Asher Gamedze

At this year’s Jazzfest Berlin, the Cape Town based drummer and composer Asher Gamedze presents his acclaimed 2020 album “Dialectic Soul”, a searing and soulful act of musical resistance against colonialism and capitalism. Besides his musical work, Gamedze is active as a scholar, educator and cultural worker involved with various social movements and community activists. His interests as a writer and researcher include African history, histories of revolutionary thought and practice, Black cultural production, and radical pedagogy. He has taught and tutored history at the University of Cape Town where he also worked as a researcher for a number of years.

Asher Gamedze

© Frank Schmitt

A Certain Space of Freedom and Intensity

Asher Gamedze in conversation with Christopher Hupe on his album “Dialectic Soul”, musical practices of resistance, South African jazz and the outsides of music

Asher Gamedze, at this year’s Jazzfest Berlin, you will present your internationally acclaimed album “Dialectic Soul”, which you recorded in a live session in the studio at the end of 2018 and released in 2020. Why was it important to you to do the album as a live recording?

Asher Gamedze: Well, the first thing is probably money. (laughs) I saved up and could afford maybe a day and a half in the studio. But also, I think there’s no such thing as perfection, especially in music. I’ve always been interested in the edges of music, and I like things to be raw. A lot of people will record and re-record things, and record until the horn players, for example, get something exactly right. If people know “Oh, I can redo my parts on this song if I get it wrong”, then maybe they don’t go all the way in on the first take. My intention is to get somewhere, to a certain space of freedom and intensity. The compositions are like a route to get there, they have to be articulated in a certain way, but I’m not striving for some kind of perfection. Something can happen that lies beyond being correct or not. It’s like the intensity of a live gig.

What does the title “Dialectic Soul” stand for?

I think the most immediate meaning for me relates to the idea of the dialectic, which is a concept that is prevalent in a lot of European philosophy, I guess famously through Hegel, and later, getting a different interpretation, through Marx. The idea of the dialectic pops up in different histories of revolution. But if you look at the trajectory of dialectics in European philosophy, it’s completely Eurocentric and racist. So when Marx theorised the dialectic, it’s constructed from a world view that sees Europe as the epitome of progress and really doesn’t have a sense of the historical dynamics of other societies. Yet still, a number of revolutionaries from Africa, from Asia, from Latin America have found something useful in this idea. People like Amílcar Cabral, who was a revolutionary from Guinea-Bissau, and Mao often spoke about dialectics. So, that’s the one aspect: the dialectic in the sense of all the complications and all the contradictions around that.

And then, you know, the idea of the soul, which obviously has multiple different trajectories, roots, references, symbolisms. There is soul music. And when I think of soul music, obviously I think about African American music from the Fifties, Sixties, Seventies particularly, but also, I think about soul music as a certain way of playing music and experiencing music that is much broader than the genre. I can think of a lot of avant-garde – or what gets spoken about as avant-garde music – as soul music because of how it makes me feel, or where it feels like it comes from and what it expresses. So, I guess, it’s about putting those things together. The idea of the dialectic is so interesting and intriguing to me also because of its emphasis on movement and change. And so, the dialectic soul being that soul which is always in motion, you know, and it’s moving to the next kind of thing and trying to move beyond that. It’s a speculative concept.

South African Music in this Year’s Programme of Jazzfest Berlin

Immanuel Wilkins

The young Philadelphia alto saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins presents his 2022 album “The 7th Hand” at this year‘s festival. While rooted in post-bop fundamentals, his agile music is thoroughly contemporary in its attack and range of influences, enfolding a mixture of gospel and free jazz elements into its simultaneously airy, groove-oriented aesthetic. Wilkins composed the album drawing upon religious experiences among other things, invoking the notion of musicians being mere vehicles for a higher source of inspiration that takes over.

Immanuel Wilkins

© Rog Walker

Immanuel Wilkins in conversation with Peter Margasak about his current album, his musical beginnings at church and the relevance and irrelevance of terms like spiritual jazz and Black radicalism

Immanuel Wilkins in this Year’s Programme of Jazzfest Berlin

Matana Roberts

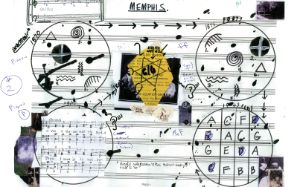

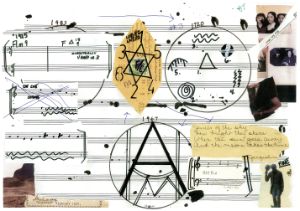

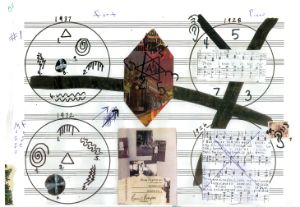

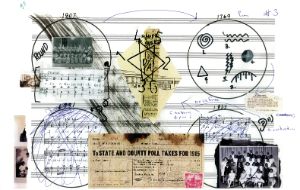

The Chicago reedist, composer and visual artist Matana Roberts (they/them) returns to Jazzfest Berlin with the European live premiere of “Coin Coin – Chapter Four: Memphis”, the latest release within a projected 12-part exploration of sonic ethnography that melds their own genealogical research with history – and has been critically acclaimed for its aesthetic originality and narrative power. A selection of graphic scores gives insight into the artistic process related to the fourth “Coin Coin” chapter. The album explores Roberts’ family roots in Memphis, Tennessee, one of America’s most important musical cities, through the lens of a relative known as Liddie, who experienced the pain and terror of racism first-hand, as her father was murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Matana Roberts

© Brett Walker

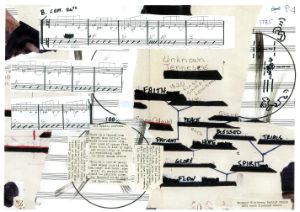

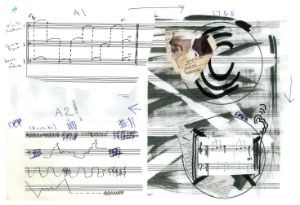

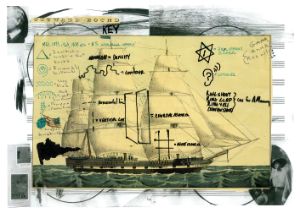

Excerpt from the score of “Coin Coin Chapter Four: Memphis”

© Matana Roberts

“At my artistic core, I am firmly dedicated to creating a unique and very personal body of sound work that speaks to, and reminds people of all walks of life to reach, stand up, give voice, regardless of difference, created from mere labels of intellectual classification. In my ideal world the idea of ‘difference’ is an illusion designed only for modern economic division and elitist intellectual hierarchy. Through my life’s work, I stand creatively in defiance.”

Matana Roberts

Excerpts from the Score of “Coin Coin Chapter Four: Memphis”

Matana Roberts in this Year’s Programme of Jazzfest Berlin

2

FreedomofSound

Sonic Explorations and Genre Transgressions in European Improvised Music

For a long time, European jazz was a phenomenon that operated almost exclusively within the parameters of established American traditions. The first significant impulses with which European musicians inspired the international jazz community can be traced back to the free jazz movement of the 1960s and 70s. Since that starting point, improvised music in Europe has taken on a burgeoning plurality of forms and has come to epitomise the creativity not only of Berlin. In two picture series we show scenes and locations of improvised music in Berlin: then and now. Julia Neupert’s essay takes a personal look at the beginnings of European free jazz and Peter Margasak shares his subjective impressions of Berlin’s musical landscape from the perspective of an American who moved here from Chicago several years ago and can hardly spend a day in either city without plunging into the bustling life of its vibrant creative scene. A series of videos from associates of the Umlaut collective will also whet your appetite for their entertaining and virtuosic stylistic disruptions at Jazzfest Berlin 2022 as part of “Umpire Jumble”.

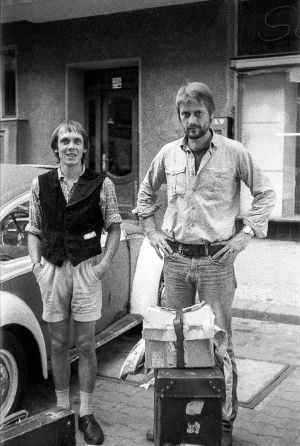

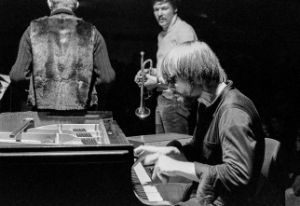

Peter Brötzmann Group: Fred van Hove, Don Cherry, Peter Brötzmann. Workshop Freie Musik, Akademie der Künste, 1971

Photo: Werner Bethsold / FMP-Publishing

Markus Müller (Ed.): “Free Music Production. FMP – The Living Music”

The Berlin-based music label Free Music Production (FMP) made a significant contribution to the production, presentation and documentation of free jazz and improvised music in Europe from 1968 to 2010. In his book “Free Music Production. FMP – The Living Music” – based on conversations with key protagonists such as Peter Brötzmann and Jost Gebers – Markus Müller tells the story of a musicians’ initiative that emerged in the context of the 1968 ideals of self-organisation and self-determination and would continue to form part of an international network for over 40 years. Thanks to unrestricted access to the FMP Publishing Archive in Borken, the book includes previously unpublished documents and photographs from the history of the FMP.

Photo Series: Berlin as a Hotspot of Early Free Jazz in Europe

Ever since the late 1950s, musicians have made repeated attempts to determine their production and working conditions themselves. When the organisers of the Berliner Jazztage, today’s Jazzfest Berlin, cancelled their invitation to the saxophonist Peter Brötzmann when he could not guarantee that his group would perform in black suits in 1968, his response was to organise the first Total Music Meeting (TMM) together with the bassist Jost Gebers. Within a very short time, FMP developed into an international hotspot for contemporary and, in the early stages, sometimes highly controversial improvised music. With a series of images based on Markus Müller’s recently published book “FreeMusic Production. FMP – The Living Music”, we provide an insight into one of the key centres of European free jazz in Berlin.

FMP-Associated Musicians in the Programme of Jazzfest Berlin

More than a Historical Episode

Music journalist Julia Neupert on the beginnings of and her personal encounter with European free jazz

“Everything except free jazz!” Anyone describing their musical taste in these terms (and a lot of people do!) is trying to make two things unmistakably clear: 1. I’m incredibly open and that’s why I’m interested in lots of very different things. 2. I can tell the difference between sound and noise and that’s why I know that free jazz isn’t actually music, and definitely not jazz.

Why is this the case? I have no idea. The first time I experienced this music (Ernst-Ludwig “Luten” Petrowsky at the Mensa in Rostock, some time in the late 1980s) I found the experience shocking in a positive way: powerful, cheerful and at the same time wonderfully ferocious. It probably desensitised me early on to all kinds of allergies to free jazz.

These had famously appeared in the early years of the “New Thing”, when even serious critics screamed hysterically when it came to the music of Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Jeanne Lee and others. This hysteria was typified by the shrill tone with which the saxophonist Klaus Doldinger indirectly accused his colleague Peter Brötzmann of being a charlatan in the now legendary WDR TV broadcast “Free Jazz – Pop Jazz” in 1967. Brötzmann’s reaction was simply to recommend in the gentlest of voices: “Just sit there and listen!”

I did not personally witness those times, but it does seem that the strong polarisation within free jazz in those days also manifested itself in Europe. The opposition to this music was so strong, yet it held such a powerful attraction for those who thought they heard in it the sound of revolt against everything that was conservative and narrow-minded. Just as in the USA free jazz was associated with the civil rights movement, its European equivalent was located in the protest culture of the ‘68 movement. And this was true of both Western and Eastern Europe. Those who have written about this include Harald Kisiedu in his excellent book “European Echoes: Jazz Experimentalism in Germany, 1950–1975”. Here he also demonstrates that the theory of the radical “emancipation” of European free jazz from its origins in the USA is only partly true. On the contrary, most of the early free jazz pioneers in Amsterdam, London, Warsaw, Wuppertal, West and East Berlin felt inspired by the American avantgarde and many of them had accumulated years of experience playing in Dixieland, swing, cool and hard bop combos.

These European protagonists ultimately discovered that free jazz gave them space to play more personally than before. The challenge was to “play yourself!” – partly because this music could not work any other way: you can’t simulate expressiveness.

At the time, different musicians in different places took their inspiration from a wide range of sources, whether these were in new music, in Fluxus or in the traditional music of their respective regions. A transnational network evolved, within which Amsterdam with the Instant Composers Pool (ICP) and West Berlin with Free Music Production (FMP) became the most visible but by no means the only centres.

Anyone who listens more closely will soon recognise that free jazz in the Europe of the 1960s to 1980s did not just represent a game of breaking things up, it also contained elements of humour, ballads, theatre music and protest songs. In any event it has since proved – quite robustly – to be more than purely an historical episode. Its vehemence and openness have fused into a musical attitude that is expressed in many forms – and can still provoke powerful emotions.

I don’t listen to everything, but I definitely do listen to free jazz!

Sven-Åke Johansson: “Liberation”

music = manifestation of all things audible

notes & noises & silence

how it is made is just as important as the result

music is visible

pauses are audible

instruments are not mastered

they are tried out, explored and played with

it’s an experiment every time

every kind of playing is correct

playing badly is still plaeyng

bad instruments are ok

good instruments aren’t bad either

anyone can play

music is existential

we have problems

of our own and between each other

we show that

problems do not have to be eliminated

we make ourselves mutually transparent

internal change brings about external change

1 music: playing existence – not playing over it

2 music: showing the way we are

3 music: activity/creativity/play/therapy

Befreiung

© Sven-Åke Johansson

Umlaut

In a similar manner to the FMP’s members 50 years ago, the musicians of the Umlaut collective joined together to establish independent production opportunities giving them creative freedom. The collective was born in 2004 in Stockholm, and then opened two branches in Berlin and Paris. It currently involves about ten musicians in its daily activity. “Transformation of sound” is the motto around which they gathered to produce records, organize concerts, discover new artists and play music together. Through all its various activities, the collective works to spread a music that is too rarely shared and discovered, fighting against the partitioning between the different contemporary musical practices.

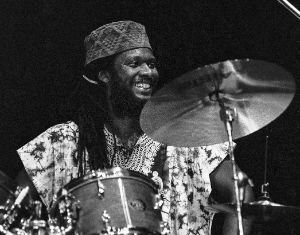

Umlaut Big Band

© Léa Lanoë

Joel Grip on the Umlaut Collective and Their “Umpire Jumble” at this Year’s Jazzfest Berlin

For more than three hours, three ensembles from the Umlaut universe will share and play the remodelled stage area of the Festspielhaus in a special performance titled “Umpire Jumble”: Sven-Åke Johansson’s agile trio with saxophonist Bertrand Denzler and Joel Grip on double bass, the quartet Die Hochstapler presenting their spontaneously programmed and arranged post-bop, and finally, to celebrate and dance along, the Umlaut Big Band with a swinging set including some special contributions.

Musicians from the Umlaut Collective in this Year’s Programme of the Jazzfest Berlin

One of the Most Cosmopolitan Cities in the World

Peter Margasak on European jazz and today’s creative music scene in Berlin

When jazz first took root in Europe it was often within countries where expat musicians from the US had settled, exerting a profound influence on such locales, whether Dexter Gordon and Don Byas in France, Ben Webster and Kenny Drew in Denmark, or Bill Barron and Red Mitchell in Sweden. The scenes in those places were strong, but for decades the metric for quality was always how close players in those countries sounded like Americans. After living in Europe for more than four years I hear an ineffable quality to American jazz when I make trips back to Chicago or Philadelphia, but what about the ineffable qualities in the music created in Berlin or other parts of Europe? Now that we’re well into the music’s second century such a qualitative scale ought to be retired.

The most exciting music on this continent – and there’s never been so much excellent, interesting work related to jazz and improvised music in Europe as there is now – shouldn’t be held to some dusty standard from an ocean away. Decades ago European musicians began developing their own language, pushing away from American jazz orthodoxy to find new pathways. That began happening in Berlin in the late 1960s, with a free jazz movement that felt no need to retain a blues foundation and instead privileged ideas from European music. These days Berlin is one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world and the astonishing music community here – which is actually many different, overlapping musical communities – collides ideas from all around the world, finding points of intersection and disruption in endless traditions. There are still countless of musicians in Berlin and the rest of Europe that subscribe to the old American conventions, and while some of them do it exceptionally well, they’re not really propelling the practice forward. Instead, we have a giant professional class that finds satisfaction in honing age-old skills. But in most cases, those aren’t the musicians who will leave their mark.

The diversity of activity in Berlin is dizzying and almost impossible to keep tabs upon for the open-minded listener. The city’s free improvisation scene has been duly celebrated around the world going back decades, but these days much of the excitement comes when musicians from other traditions – whether neue musik, various ethnic traditions, or electronic realms – engage in the practice. And then there are free improvisers who stretch out, driven by curiosity and study, to enfold once alien conceptions into the fold. As Berlin’s population has grown more diverse, so too has its music scenes. As I sit writing this the weekly update of the Echtzeitmusik calendar has turned up in my inbox, and the listings present a cornucopia of adventurous sounds happening in Berlin, but this calendar is but a tiny fraction of what’s happening here, the best of which tends to engage not only in the music that happens all around us in this city, but with all sorts of international activity.

When the European media suggests that American jazz and improvised music is moribund, it’s no less ignorant and chauvinistic than the US voices that have long given short-shrift to music made over here. Why not celebrate that diversity, especially in a city like Berlin that feels like a melting pot as much as anywhere on the planet?

Photo Series: Scenes and Spaces of Improvised Music in Berlin Today

The pictures of Berlin photographer and music fan Cristina Marx document the creative jungle of Berlin’s live music scene. Her series of photos conveys visual impressions of the vast range of improvised music in Berlin today and the places it is played.

3

ListeningtotheField(s)

Folk Traditions and Cultural Encounters in Contemporary Jazz and Improvised Music

The influences of regional music traditions within this year’s Jazzfest programme are as manifold as they are aesthetically inspiring. They range from the songs of Northern Italian female field workers through the distinctive tone qualities of traditional instruments – from Romania, Poland, Armenia and beyond – and on to musical folk traditions from all over the world. Henning Bolte takes the beginnings of ethnomusicological field research in Eastern Europe and the Black Sea region as the starting point for an essayistic journey through the history of the reciprocal relationship between jazz and folk music evident in the contributions to this year’s Jazzfest Berlin. In a series of short videos, musicians from the programme talk about their different relationships with folk music from a wide variety of regions. Issues of identity and tradition are raised along with their specific approaches to ways of making music that often rely solely on oral traditions: from learning by ear via recourse to ethnomusicological methods to the creative use of field recordings and experimental techniques. And in a video interview, the Chicago based AACM artist Ben LaMar Gay, who seems to absorb the musical languages and cultural influences of his fellow musicians like a sponge in his multistylistic creations, shares some of the mysteries of his creative process.

“I’d listen to a lot of jazz and bebop records, too. […] I tried to discern melodies and structures. There were a lot of similarities between some kinds of jazz and folk music. […] ‘Ruby My Dear’ by [Thelonious] Monk was another one. Monk played at the Blue Note on 3rd Street with John Ore on bass and the drummer Frankie Dunlop. Sometimes he’d be in there in the afternoon sitting at the piano all alone playing stuff that sounded like Ivory Joe Hunter-a big half-eaten sandwich left on the top of his piano. I dropped in there once in the afternoon, just to listen-told him that I played folk music up the street. ‘We all play folk music,’ he said. Monk was in his own dynamic universe even when he dawdled around. Even then, he summoned magic shadows into being.“

Bob Dylan (“Chronicles. Volume One”, p. 94-95)

A Dynamic Process of Continual Interactions

Henning Bolte on traces, techniques and tensions in the encounter of jazz and folk

The term “folk music” awakens numerous associations, images and emotions that are both appreciative and less appreciative in nature. In any event, folk traditions that have been formed in regional and local cultures over long periods are the origin and basis of all forms of music, ranging from sacred to classical (from Bach to Bartók and Berio) and from jazz to pop and rock – whether they have been used consciously or their effects have been absorbed subconsciously. They can be recognised more or less directly or made recognisable with the help of studio technology. Even what we call jazz, while evolving into an urban music practice, has deep inherent links with various folk traditions.

Folkloric influences in music are not to be underestimated and keep on resurfacing in contemporary music. The absorption and adaptation of folk traditions take place in a dynamic process of continual interactions, transformations, transmutations and impulses in which the effects of both internal music and external musical forces are manifest. They operate within a vital force field filled with thefts, distortions, trickster-like resistance, identificatory anchor points, escapism and reassuring references.

Jazzfest Berlin can look back upon the most varied approaches within this force field. And there are also numerous examples in this year’s edition. The focus of the 2022 edition of the festival is directed eastwards – on folk traditions in Armenia, the lands around the Black Sea, in Transylvania, Poland and the Ukraine. As a consequence of the deadly acts of war since 24 February this year, the East has increasingly become the object of our attention and our cultural understanding. This compensates for a lack of recognition (that also applies to music) that experiencing a variety of approaches to the rich folk traditions from this region at the festival will not entirely resolve but which nevertheless can be bridged by numerous living impressions.

Ben LaMar Gay

Ben LaMar Gay thinks of his music as a medium of storytelling. The Chicago based composer, cornet player and multi-instrumentalist is a member of the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians), and spent several years abroad drinking up the sounds and culture of Brazil, but it seems like whatever place he goes to he absorbs its sonic essence, enfolding within an ever-widening aesthetic. He delivered a stunning survey of his work on last year’s “Open Arms to Open Us”, forging an alchemic blend of post-bop, soul, gospel, Carnival music, blues and more that can’t be meaningfully parsed. For his Berlin debut, LaMar Gay has assembled a quartet of close co-conspirators that promises to distill his vision even further.

Ben LaMar Gay

© Alejandra Ayala

“My relationship with stories and folk tales … it’s just dealing with memories, transformed into something else and passed on to different communities. After researching and learning […] and being welcomed into different communities, I started matching dots, […] and everything would come back to these old folk tales or traditions, or maybe ancient memories.”

Ben LaMar Gay

Ben LaMar Gay in conversation with Peter Margasak on musical influences and transformations within his creative working process

Ben LaMar Gay in this Year’s Programme of Jazzfest Berlin

Contributors

Henning Bolte

Henning Bolte is a jazz journalist and visual artist. He works as a curatorial adviser for the Jazzfest Berlin.

Christopher Hupe

Christopher Hupe works as a dramaturg for Jazzfest Berlin since 2019.

Peter Margasak

Peter Margasak is a long-time music journalist (for Chicago Reader, Rolling Stone and The New York Times, among others), who has also programmed the weekly Frequency Series at Constellation in Chicago since 2013. He works as a curatorial adviser for the Jazzfest Berlin.

Julia Neupert

Julia Neupert is a jazz editor and moderator at SWR2. She lectures on jazz history at the Bern Academy of the Arts.