Opening Theatertreffen 2023

© Berliner Festspiele, photo: Fabian Schellhorn

Who Has the Privilege to Not Know?

Answers, Considerations and New Questions

The question of “Who has the privilege to not know?” was of special significance during the concept phase of this year’s festival edition. With no claims of being complete, this Digital Guide provides room for answers, viewpoints and considerations of young culture makers who attended the 2023 Theatertreffen in the context of the formats International Forum and Theatertreffen-Blog.

1

TheHumanConceptofPrivilege

Through the Lens of Place

Luke Casserly

Luke Casserly is a multidisciplinary performance maker originally from Longford, Ireland. His work weaves together environmental research, documentary, sound art, and site as a way of carving out space for new possibilities to emerge between live performance and physical landscape. To date, his projects have brought audiences through city streets, back gardens, train stations, beaches, and a bog in the Irish midlands. These works have led to the creation of a network of wildflower meadows across Ireland (“1000 Miniature Meadows”, 2020) and the planting of 1000 indigenous trees in the Irish midlands (“Root”, 2021). Often using autobiography as a starting point, his work attempts to stretch out new conversations around our human impact on the environment.

Luke Casserly was recently selected for the Norman Houston Multi-disciplinary Commissioning Award with Solas Nua in Washington DC. He holds a BA in Drama and Theatre Studies from Trinity College Dublin, and is Associate Director of Pan Pan Theatre.

Luke Casserly

© Ellius Grace

By Luke Casserly

I believe it is important to accept the various privileges one possesses – this acceptance gives us a better understanding and awareness of who we are, and allows us to create a more fair and transparent society. I, like many others, possess various privileges because of factors outside of my control. I am male, white, from a lower-middle class family in rural Ireland. I could talk about any number of these specific privileges and how they have shaped the reality of my life. However, I don’t think privilege is confined only to the human experience. I have been thinking a lot recently about the landscape where I grew up and how it has suffered greatly over the past 20 years as a result of the peat harvesting industry. The sustained extraction of peat over many years has caused irreversible damage to the biodiversity in this place. It has made me consider our human relationship to privilege through the lens of place. As humans, we possess an inherent privilege in that we can speak. We have a voice. If someone is being abused or hurt in some way, it is possible to communicate what is happening, and make it stop. Our landscapes don’t have this privilege, they remain silent and voiceless through, quite often, centuries of hardship. In this neutrality, our landscapes do not know the human concept of privilege in itself – they don’t have a gender, a class, a sexual orientation. They negate the very concept of privilege in a way, in their “not knowing”. I think privilege is one of the most important things we need to wake up to and discuss in our society. However, I also think there is a lot to be learned by returning to our physical landscapes to hear what they might have to say, or offer to the conversation.

The Midlands Bog landscape located in Longford, Ireland

© Luke Casserly

2

ThePrivilegeNottoKnow

Questioning the Palette

Laura Kutkaitė

Laura Kutkaitė

© Elena Krukonyte

Laura Kutkaitė, born 1993, is a Lithuanian theatre director. She graduated in Choreography and Philosophy before studying Directing at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre. Her first work at the Lithuanian National Drama Theatre, “The Silence of the Sirens”, mixed mythology with documentary stories from actresses abused during creative processes. With it, she has won the main prize of Fast Forward – European Festival for Young Stage Directors 2022.

Her emerging voice reflects body, gender, social exclusion and identity control. Viewing feminism as intellectual commitment, every creation becomes an attempt to loosen the screws of patriarchy and empower women. She values vulnerability and focuses on creative process: the internal processes are often transferred on stage making the line between fiction and documentary intentionally blurry.

Currently, she is preparing for her upcoming works in Lithuanian National Drama Theatre and Staatsschauspiel Dresden.

By Laura Kutkaitė

I was spending time in various workshops with people from different fields, not just performing arts, and in a month I learned more about theatre than I ever had by being directly in it or studying it. Theatre is people. The matter is – and here comes an unpopular opinion – that it is getting more and more common to view directing or acting only as a profession, to have more and more (healthy) boundaries in theatre. We think that this is in order to escape abuse, but what if we only end up escaping ourselves?

This question and all possible answers to me are closely connected to the question “Who has a privilege not to know?”. My first anarchic instinct is to say, “Well who has not?”, in a few seconds I start to feel bad about it. I start thinking of my interview with a quote for its headline “I want to be able not to know”. This question is very personal to me and yet so universal during these trying times. Being able not to know is freedom to me. Not to know black or white and to throw yourself deeper into theatre, not creating rules around it. It is freedom when I think of creative process and the privilege of a director not to know. Finding actors to work with who allow you not to know is a beautiful, beautiful thing. I hope everyone could have a privilege not to know.

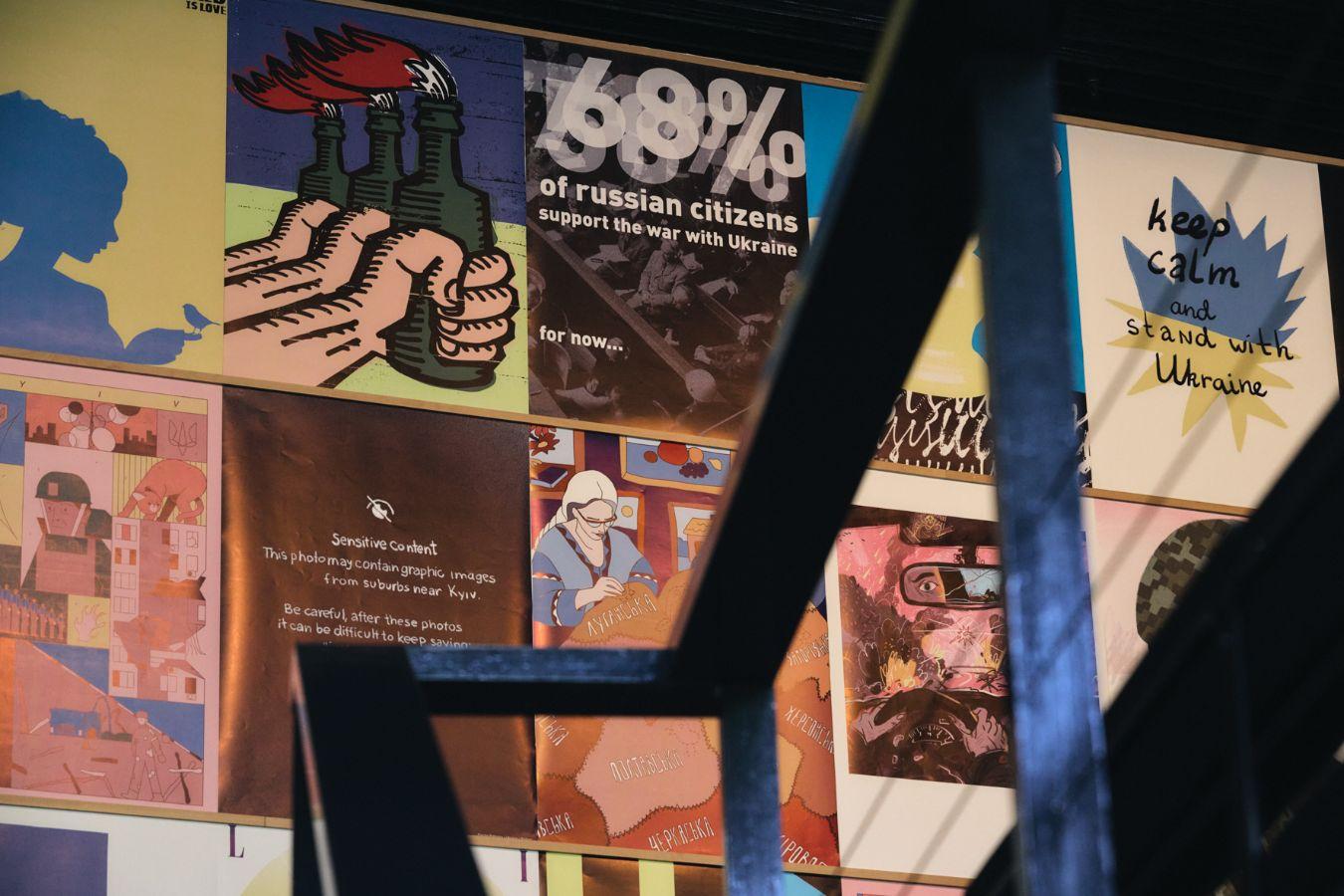

This is utopia. Our harsh contemporary reality does not and probably will not allow us not to know. But is not knowing the same as being willingly ignorant? We have Russia’s war against Ukraine, climate change, just to name a few. It is impossible to stay ignorant whether you are a person or an institution such as theatre.

Poster exhibition “War on Distance” at the 2023 Theatertreffen

© Berliner Festspiele, photo: Fabian Schellhorn

3

TheDiscourseonPrivilegeasaZombie

I’d Prefer to Return the Question

Frederik Müller

Frederik Müller is a multidisciplinary artist between stage, writing and video. He works with different media on radical trans feminism, girl culture, queer Marxism and Britney Spears. Together with Banafshe Hourmazdi and Golshan Ahmad Hashemi, he was part of the performance collective Technocandy from 2013 to 2019. He has been writing for Missy Magazine since 2017.

In 2021 Frederik Müller was a fellow of the Cultural Foundation of the Free State of Saxony and worked on his novel “Heaven’s” at the Prague Literature House of German-language authors.

In 2023, his play “Livename” premiered at the Chawwerusch Theater (Herxheim). He is also touring with Rotte Nomi with the work “Der deutschen Mutter”.

He studied Directing for Theatre at the Academy of Performing Arts Baden-Württemberg (graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 2015) and attended the training Politisk Scenkonst Utbildning at Teater Tribunalen in Stockholm from 2013 to 2014.

More information you can find on his website.

Frederik Müller

© Rotte Nomi

By Frederik Müller

When I am asked about my attitude to not knowing as privilege, I feel that this question is a trap door. With a wolfish smile, it invites the feminist dedicated to identity politics to explain concepts like privilege and knowledge for the 100th time. She will explain dominant culture, knowledge for domination, community. But the question highlighted by inverted commas is not the actual question – the actual question asks for my attitude towards it. This is where the trap door opens for the feminist. She has exhausted herself, regulated emotionally, dimmed down intellectually, denied her own artistic brilliance and taught a beginner’s course in anti-discrimination. She has no attitude left, she plummets to the depths.

The question before the question – the actual question, that is – is directed at those who can answer it. Those for whom it is of no consequence whether their attitude is this or that. Those who are not essentially involved. Those who don’t care whether they know or not.

The discourse evoked by this question is a revenant.

Ten years ago, for example, in 2012, the group Bühnenwatch was founded as a response to resistant racists at Berlin’s theatres. Black-facing, racist language, the refusal to hire Black artists etc. One of the prominent founding members was Sharon Dodua Otoo. The defensive howls of the racists were the same back then: On the one hand, we didn’t know that it’s racist to paint yourself Black, and on the other hand we had no choice because we don’t know any Black actors who could play Black people, etc. etc. It’s impossible to reproduce the whole debate here; in any case, it has been repeated umpteen times over the following years, although it was already older than the hills in 2012.

I mention this example to give a timeline of the discourse on privilege in the German-language theatre world. It’s a zombie. Dead from the outset, it still wanders among us. As a political artist, you are faced with the fact that the majority will fight you tooth and nail until it finally absorbs you.

The fact that this question is an application requirement for the International Forum therefore brings me to the issue of visibility. Our debates have slipped from activist circles into high culture – did they bring us along? When I write “us”, I mean a variety of groups of people, social groups, whimsical marginals; what we have in common is that we are being systematically classified by the culture industry in a certain way.

Hypervisibility is something that Black artists of all genders and transgender artists of any positioning (white, Black, PoC, Jewish…) have in common. All eyes on you, but they can’t remember your name. All eyes on you, but you won’t be listed in the credits. All eyes on you, but when someone strikes a blow, nobody saw. What should I answer? I’d prefer to return the question. Why was it asked? By whom? Etc.

Read More on the Topic of Privilege

In the Theatertreffen-Blog Klaudia Lagozinski reflects on the accessibility of the events to a wide audience, Anastasia M. E. Gornizki shares her impressions of the seven-hour opening night, Günther Mailand thinks about capital through the lens of culture and culture through capital and Antigone Akgün asks the fundamental question: What are we doing here as cultural journalists?

Opening Theatertreffen 2023

© Berliner Festspiele, photo: Fabian Schellhorn

4

AnAnswer’sAbsence

The Threshold of Knowing

Tyler Cunningham

Tyler Cunningham, born 1996, is a performance maker and writer, and he is currently on a Fulbright Research Grant based in Stuttgart. His work thinks through the interstices between artifact and artifice, and his current projects use machine learning to imagine the speculative worlds possible by the gaps that litter history. Specifically, he is looking for his unaccounted-for ancestor Abraham Alter.

His projects have been shown with the collectives he co-founded PROMPTUS and NEL2R, most recently with the project “the machines that hold us” at The Music Gallery and as an Artist in Residence at Critical Mass: A Centre for Contemporary Art. He has also written performance reviews and essays for Refuze Review, Peripheral Review and CultureBot.

He studied at the Juilliard School, where he received the John Erskine Prize in Scholastic and Artistic Achievement, and he did graduate work at the University of Toronto and is currently at the State University of Music and the Performing Arts Stuttgart.

Tyler Cunningham

© Nicholas Kotoulas

By Tyler Cunningham

Of course, ignorance is the fertilizer for complicity to sprout. The mythology of “purity”, or some sort of a priori sensibility in which one does “not see race” and is somehow objective and ahistorical, is predicated by the ignorance about how cultural bias and intergenerational knowledge, oftentimes in the form of trauma, is interwoven into the fabric of both individuals and institutions. If one cannot, or chooses not to consider how these cultural and historical narratives shape biases in regards to race, gender, sexual orientation, accessibility, and socioeconomic status among many other factors, then it is more likely than not because they do not have to: a privileged position.

Yet, if there’s space for this possibility, we would be remiss to always group a concept of “not-knowing” to “privilege”. Missing archives, forgotten histories, displaced family members with no record: which episteme earns a privileged position in this archive?

My great-great-uncle Abraham Alter was born in 1909 in Sokolow Podlaski, Poland. After his father and sisters had emigrated to the United States in 1920 because increasingly anti-Jewish pogroms developed in the area where he lived, Abraham, his brother Jeremiah, and his mother Lena immigrated to the United States via Ellis Island in 1923. From what we could gather from our research into his immigration papers, Abraham had an intellectual disability, denoted as “mentally feeble” in a document indicating a medical hold. Abraham was not allowed into the United States and was deported back to Poland when he was 14 years old. Jeremiah fortunately accompanied him, but their mother remained in the USA. Jeremiah returned to the United States two years later, leaving Abraham to live with his uncle Meilech Alter. We found death records of Meilech Alter and the rest of his family that indicated that they passed 13 years later at the Chelmno concentration camp. Yet, we did not find and still have not found anything about Abraham’s death records, nor have we located any indication whether he left his uncle at some point over the thirteen year period. We are only left with one photo of him.

Every time I look upon this photo of Abraham, I feel as if I know less and less about him. I sympathize with Orpheus, who turns to Eurydice to make sure she is behind him while leaving the underworld, only to find her disintegrate before his eyes: turning to this photo of Abraham does the same for me. Is not knowing what happened to Abraham a privilege? Is it an intergenerational form of burden, even trauma? Perhaps these questions are meant to be rhetorical and open-ended.

Theatertreffen 2023

© Berliner Festspiele, photo: Fabian Schellhorn

On the Formats

The scholarship programme of the International Forum gathers international artists to see art together and work on the future of the theatre. The authors and theatre enthusiasts of the Theatertreffen-Blog provide critical coverage of the festival. Many thanks to everyone for contributing to this Digital Guide.