Exhibition texts

Daniel Boyd: RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION)

Introduction

RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION) presented an overview of the work of Daniel Boyd, characterised by a visual technique that unsettles Western knowledge production. Boyd’s practice offers fragmentary ways of seeing that at once expose and obscure. Since the early 2010s, the artist has made paintings punctuated with dots – which he terms “lenses” – that run across their surface. In interplay with black paint, these dots produce a trembling overlay.

Boyd draws on such sources as Indigenous knowledges, Gestalt theory and his own ancestral family histories while challenging the colonial narrative of Australian nation-building. The writings of poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant provide an important theoretical framework for his practice.

Non-First Nations people erroneously use “Rainbow Serpent” as a blanket term for various creation stories from distinct First Nations communities in Australia. Boyd included “(VERSION)” in the exhibition title to highlight the nuance and diversity of First Nations’ individual cosmologies.

Different entryways into RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION) encouraged multiple paths through the exhibition. This non-linear display mirrors Boyd’s defiance of fixed categorisations that characterise cultural homogenisation.

“Trembling thinking is the instinctual feeling that we must refuse all categories of fixed and imperial thought.” — Édouard Glissant

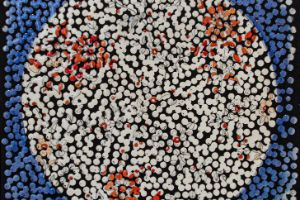

Untitled (FDWHBFTU)

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

The painting depicts a dinner plate once used in Robert Louis Stevenson’s house in Samoa, now held in the University of Sydney’s collection. The Scottish novelist settled on the Samoan Islands in 1889 and lived there until his death in 1894.

Like Boyd’s paintings evoking the Necker cube – an optical illusion that has been used to demonstrate the elasticity of human perception – the plate paintings invited and produce different ways of seeing by the repetition of the same motif throughout the exhibition, varying in scale and colour.

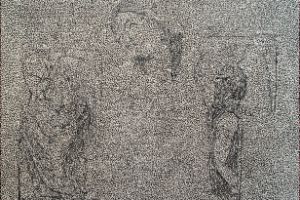

Untitled (MLBATS)

The painting shows a view into a mangrove forest along the coast near Gimuy/Cairns in North Queensland, Australia, where Boyd grew up. The source image of this painting is a photograph by Boyd’s nephew. Mangroves live on coastlines between the high and low tidelines. Their roots grow below and above the water’s surface. Once a seed falls into the water it floats until it finds solid ground to grow new roots. The dense canopy of interlacing branches makes it impossible to discern single branches; similarly, the tree’s shoreline position unsettles the division between land and water.

The mangrove can be seen as a symbol for Boyd’s approach to interconnecting narratives that travel through time and space. It also reflects his painting technique that oscillates between what is seen and what is protected from view.

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

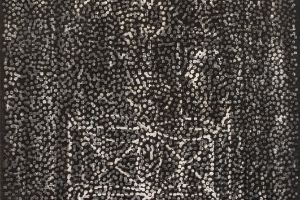

Untitled (TDHFTC)

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

This painting depicts a photograph of Boyd’s sister getting ready for a dance ceremony. The dance ceremony is one example of the many ways Western culture was imposed upon First Nations children. Between the mid-19th century and the 1970s, they were forcibly removed from their families and communities by the Australian government. These children, known as the “Stolen Generations”, were placed in foster homes, governmental institutions and church missions, where they were forbidden to engage with any form of culture related to their First Nations heritage.

By choosing an image of his sister continuing to perform the dance forced upon the “Stolen Generations”, Boyd challenges questions of cultural heritage and authorship, while also showing how re-appropriation can be a form of resistance.

Untitled (INYIM)

The source of this painting is a 1961 photograph of Queen Elizabeth II dancing at a ball with Ghana’s president Kwame Nkrumah, originally printed in the London newspaper The Times. The British monarch visited Nkrumah in the capital Accra four years after Ghana gained independence from British rule and became part of the British Commonwealth. During the Cold War, US and British governments were concerned about Nkrumah’s socialist leanings and feared he would ally Ghana with the Soviet Union.

The photograph of two heads of state dancing together was widely circulated in the media. It was politically instrumentalised by the British government to portray their meeting in Ghana as a victory for the US and Britain, away from the threat of Soviet alliances.

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

Untitled (BBBTH)

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

The image depicts Bob Maza, Gary Foley, Bindi Williams and Aileen Corpus. They were members of the National Black Theatre on Gadigal and Wangal Country, Sydney.

After he had visited the National Black Theatre in Harlem, New York, in 1970, Bob Maza co-founded an eponymous theatre company on Gadigal and Wangal Country, Sydney. The group started to organise street performances during the Aboriginal land rights movement, addressing discrimination against First Nations peoples and their land rights claims. In collaboration with the Nimrod Theatre, they produced Basically Black, satirical and political sketches first broadcast on television in 1973.

The National Black Theatre on Gadigal and Wangal Country, Sydney, ran until 1977. It played a crucial role in using performance art as a form of political activism and resistance for First Nations peoples.

Sir No Beard

In his early No Beard series (2005–2009), Boyd reworked portraits of colonial instigators. Here, Boyd appropriated a portrait of botanist Joseph Banks, painted by Thomas Phillips in 1810 and held by the National Portrait Gallery in London. Banks accompanied James Cook in his HMS Endeavour voyage.

In the late 18th century, following Banks’ instructions, breadfruit plants were transported from Tahiti to British colonies in the Caribbean to provide cheap food for enslaved people working in British plantations. Here, Banks poses next to a decapitated head floating in a specimen jar: a self-portrait of Boyd himself. The head references Pemulwuy, a Bidjigal leader and key figure in the First Nations resistance against colonial rule on Gadigal and Wangal Country, Sydney. After being killed by the British in 1802, Pemulwuy’s decapitated head was sent to Banks in London.

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

Untitled (ATOKRTTP)

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

This painting’s source image comes from an early 19th century bulletin related to the Greek Parthenon marbles’ entering the British Museum’s collection. In 1801, they were taken from the Parthenon temple in Athens by Lord Elgin and brought to London, where they remain today. Since 1983, Greece has actively sought their return.

Untitled

This is a portrait of Édouard Glissant, a philosopher and poet from Martinique. Glissant is known for his concept of “the right to opacity and difference.” Through imperialism and colonialism, Western ideas of transparency were imposed around the world. For colonised or formerly colonised peoples, however, transparency often led to categorisation and stereotyping. Instead, Glissant proposed a model of global exchange that does not erase cultural diversity but embraces difference.

Glissant’s thinking has come to be an important reference for Boyd. In his painting, light and darkness are valued equally. By focusing on the translucent dots – which the artist terms “lenses” – as well as the dark spaces in between, Boyd suggests that knowledge is fluid and fragmentary.

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

Untitled (WTEIA2)

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

What may appear to be an abstract shape is in fact a cartographic tool called a Rebbelib. Rebbelibs are maps made in Majel/Marshall Islands to chart swells, currents and islands in order to navigate the Great Ocean.

They are made from shells and wooden sticks lashed together with coconut fibres.

Boyd first encountered the device in the archives of Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island (1883). It was thus stored in a context alienated from the map’s original cultural use and its practitioners.

Boyd considers both the source material itself and the contexts where it is found. His work addresses the dislocation of cultural materials and the dispersion of local knowledge that resulted from colonisation.

Untitled (FAIALSD)

In his work, Boyd references his ni-Vanuatu heritage, as well as the trade of enslaved people that occurred between Vanuatu and Australia. The history of slavery has long been omitted from dominant narratives about the colonisation of the Australia-Great Ocean region. Boyd’s great-great grandfather was among those brought from Pentecost Island, Vanuatu, to North Queensland, Australia, in the late 19th century to work on sugarcane plantations.

This painting is based on a sand drawing from the Vanuatu archipelago, where such drawings are used to communicate and transmit knowledge amongst the multiple communities inhabiting the archipelago’s islands.

Boyd came across the Vanuatuan sand drawings on the internet, where he also found images taken by an anthropologist who added lines and numbers to the patterns of the sand drawings with the ambition to decode their structure and meaning.

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

Untitled (FOVWMYLTTL)

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

In this work, Boyd depicts the head of a statue of the ancient Greek figure Achilles in London’s Hyde Park. The victory memorial was inaugurated in 1822 to commemorate the 1st Duke of Wellington. In the statue, Achilles is characterised to represent strength and victoriousness in battle.

In contrast, Boyd is interested in another representation of Achilles: in the 5th century BCE, philosopher Zeno of Alea wrongfully argued that Achilles could not pass a tortoise in a race if the tortoise’s starting point lay ahead of his.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Zeno’s paradoxes were invoked by statisticians to calculate the risk of infectious diseases without being able to rely on detailed data. The fluidity of narratives across times and geography combines with Boyd’s interest in disrupting the distorted, patriotic image of Achilles by highlighting his vulnerability.

Untitled (NAACSHS)

This painting is based on a found academic drawing of the Apollo Belvedere, an antique marble sculpture housed in the Vatican Museums in Rome.

Boyd worked deliberately from this drawing, which represents the figure’s proportions as ideal, in order to shed light on the ways visual iconographies travel through space and time: the drawing makes accessible an image to someone who has not seen the sculpture in person. Moreover, it shows how iconography outlasts antiquity and extends to classicism and neo-classicism and beyond.

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

Untitled (PAITA)

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

© Gropius Bau, photo: Luis Kürschner

The group of four paintings is based on an early 20th century photograph of an archer from the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific. The archer resembles other mythological portrayals in the exhibition, such as the ancient Greek figure, Achilles. However, Boyd’s depiction resists the heroic stance common in classical representations of the Greek warrior. The archer in Boyd’s painting is shooting a fish in the water: his target is unseen.

This notion of gesturing towards the unseen – and, in a broader sense, towards the omitted parts of history – relates to Boyd’s painting technique. He transforms surface visuals by combining translucent dots with black interstices, resulting in works that both reveal and conceal.

Untitled

As part of his exhibition RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Daniel Boyd engulfed the building architecture in a second skin layered over the atrium and first floor windows. The atrium’s floor was covered in mirrors reflecting the existing architecture in a fragmented, everchanging image.

The installation also reflected the Gropius Bau’s past. The building was heavily damaged during a bombing raid in 1945. The traces of this attack were deliberately left visible in the course of the building’s reconstruction.

Boyd conceived this installation as a stage for a programme that played out over the time span of the exhibition.

Daniel Boyd, RAINBOW SERPENT (VERSION), Installation view, Gropius Bau (2023)

photo: Luca Girardini

Untitled (52°50’70.907“N, 13°38’18.955“E)

photo: Luca Girardini

Boyd expanded and adapted his painting technique to the windows of the Gropius Bau. The holes in the vinyl surface marked the point of difference between lightness and darkness, and served as a threshold that refracts the light, bringing the space into constant flux.