Yoko Ono in HALF-A-ROOM, 1967, installation view, HALF-A-WIND SHOW, Lisson Gallery, London, 1967, Photo © Clay Perry / Artwork © Yoko Ono

Story

Spotlight: Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono is acclaimed as a trailblazer of Fluxus, an early practitioner of Conceptual art and a radical force in performance, music, film and peace activism. This text traces key themes in her extensive body of work, highlighting pivotal moments in her life and selected works featured in the Gropius Bau exhibition YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND.

1

Beginnings

Yoko Ono was born in 1933 in Tokyo as the first daughter in an affluent household. Her mother, who came from a wealthy banking family, played several instruments and encouraged a love of the arts. Her father, a trained concert pianist, worked in the same bank as his father-in-law. During her early years, Ono lived in the United States twice, briefly, due to her father’s professional postings. Music was a constant companion throughout her childhood: she received classical training in voice, composition and piano, and was taught to translate everyday sounds into musical notation.

The Second World War left a lasting mark on her early life. In 1945, as Tokyo came under heavy bombardment, Ono and her two siblings were evacuated to the countryside, where food and other essentials were scarce. To escape the difficulties of everyday life, twelve-year-old Ono and her younger brother took refuge in imaginary worlds. Years later, Ono herself referred to these thought experiments as perhaps her first works of art.

.jpg)

Yoko Ono, Chair Piece, 1962, performed by Yoko Ono in Sogetsu Contemporary Series 18: John Cage and David Tudor, Kyoto Kaikan Second Hall, 12 October 1962

Courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation. Photo: Yasuhiro Yoshioka / artwork © Yoko Ono

“We exchanged menus in the air and used our powers of visualisation to survive.” — Yoko Ono, 1990, speaking of her 1945 experience

2

Studies and First Compositions

After the war, Ono returned to Tokyo and enrolled at Gakushūin University in 1952 to study philosophy, becoming the first woman in the department. At the end of 1952, she moved to the United States with her family and continued her education at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York, where she studied composition and literature and developed a growing interest in contemporary music.

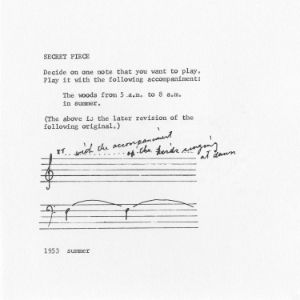

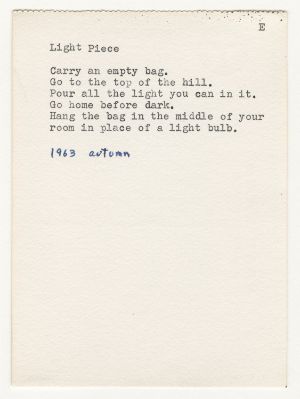

It was during this period that Ono began to develop her first compositions and experimental works with text. When she tried to notate birdsong, she found that traditional musical scales fell short. To capture the sounds more fully, she later began adding words alongside the notes. Eventually, these additions evolved into brief, direct instructions that replaced the musical score entirely.

Before completing her studies, Ono met composer Toshi Ichiyanagi and moved with him to Manhattan, where they married in 1956.

Yoko Ono, SECRET PIECE, 1953. Published in Grapefruit, 1964

© Yoko Ono

3

Chambers Street and First Events

By the late 1950s, Ono was becoming a key figure in New York City’s experimental art scene. In 1960, she rented a loft at 112 Chambers Street in Manhattan and, together with composer La Monte Young, launched a groundbreaking series of events showcasing experimental music, visual art, poetry and performance. The series offered a platform for artists exploring new forms and ideas – those working outside conventional categories of art and music. While the loft itself provided an alternative to classical concert venues: a large, adaptable space, open to experimentation and creative exchange. Ono herself performed at several concerts at Chambers Street. She also began making her Touch Poems and first presented her Instruction Paintings at Chambers Street. An expanded selection of these works was later included in her first solo exhibition, at AG Gallery in July 1961.

Yoko Ono during a performance in her Chambers Street Loft Series, 1960/61, New York

Photo: Minoru Niizuma © Yoko Ono

Chambers Street Loft Series

4

Audience and Participation

In 1960, Ono and other artists increasingly sought to create forms of art that were open and ephemeral. Rejecting static objects and conventional exhibition spaces, they tried to expand the understanding of art. Audiences were invited to participate, dissolving the distance between creator and viewer. The designer and architect George Maciunas in 1961 to 1962 would group together these practices under the name Fluxus.

Artists, composers and choreographers such as Allan Kaprow, Simone Forti – who participated in several events at Chambers Street – George Brecht, John Cage, Yvonne Rainer and others began to reject the idea of sole authorship, relinquishing control while welcoming chance, audience participation – often within the framework of events and happenings and natural processes into their work. Ono played a key role in the formation of the Fluxus movement through her ideas and the Chambers Street series. Despite taking part in several Fluxus concerts and events, she maintained a strong sense of artistic independence and never fully adopted the Fluxus label.

Chambers Street Loft Series, 1960/61

Photo: Minoru Niizuma © Yoko Ono

“Event, to me, is not an assimilation of all the other arts as Happening seems to be, but an extrication from the various sensory perceptions. It is not ‘a get togetherness’ as most happenings are, but a dealing with oneself. Also, it has no script as happenings do, though it has something that starts moving – the closest word for it may be a ‘wish’ or ‘hope’.” — Yoko Ono, 1966

5

Instruction Paintings

In July 1961, Ono’s first solo show opened at George Maciunas’ AG Gallery in Manhattan. Paintings & Drawings by Yoko Ono featured around 20 Instruction Paintings, conceptual works consisting of or accompanied by brief instructions telling viewers how to imagine or enact the piece. These works, in other words, could only be completed through the participation of audience and environment. Many instructions for paintings were spoken aloud by Ono during the exhibition.

The Instruction Paintings were remarkable in that they started out at Chambers Street and the AG Gallery, being what they were – conceptual works. Ono challenged not only the idea of the artwork as permanent and finished, but also the cultural reverence for fine art as sometimes untouchable.

Following the AG Gallery exhibition, Ono expanded her practice to larger stages, including Carnegie Recital Hall in New York City. Her focus included performance and Conceptual art.

Yoko Ono, Painting to Be Stepped On, 1961

Photograph by George Maciunas, digital image © MoMA N.Y. / artwork © Yoko Ono

6

Ono and Japan

In 1962, Ono returned to Japan to give a concert and hold an exhibition at the Sōgetsu Art Centre titled Works of Yoko Ono. The concert included A Grapefruit in the World of Park, Piece for Strawberries and Violin, Piece To See the Skies, The Pulse and AOS to David Tudor; the exhibition in the lobby included several Pieces for Chairs and Touch Poems.

Part of the exhibition was also Instructions for Paintings, 30-some short directives written on paper. These works consisted only of text; the paintings were meant to take shape in the minds of the audience. This further development in her practice marked a key step in Conceptual art, where the idea itself constitutes the artwork.

Ono ultimately stayed in Japan for two and a half years.

Yoko Ono, Lighting Piece, 1955, performed by Yoko Ono as part of Works of Yoko Ono, Sogetsu Art Center, Tokyo, 24 May 1962

Courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation. Photo: Yasuhiro Yoshioka / artwork © Yoko Ono

“Had I stayed in New York I would have become one Performance of those grande dames of the avant-garde, repeating what I was doing.” — Yoko Ono, 1994

Despite being creatively productive during this period, Ono was repeatedly frustrated that critics often defined her in relation to John Cage. In summer of 1962, she was hospitalised due to emotional distress. During this period away from public attention, she developed new performances and increasingly concentrated on her instruction pieces, which she would collect and self-publish two years later in her book Grapefruit.

Yoko Ono, Light Piece, 1963, published in Grapefruit, 1964

© Yoko Ono

Grapefruit

In 1964, Ono self-published the book Grapefruit, which includes more than 200 instructions written between 1953 and 1964. They are divided into five sections: Music, Painting, Event, Poetry and Object. Ono’s instructions can be completed by anyone, some physically, some only in the mind. Ono performed some of them many times internationally throughout her career and let others present their own variations.

Yoko Ono, Grapefruit, 1964, Wunternaum Press (the artist), Tokyo, Edition: 500

© Yoko Ono

After her self-imposed retreat, Ono found renewed drive and inspiration: she and her husband Toshi Ichiyanagi arranged for a tour of John Cage and David Tudor, and others – including herself, her husband and Toshiro Mayuzumi, and it became known as the ‘Cage Shock’. She also showed works at the Minami Gallery, exhibited at Naiqua Gallery, composed and performed the music in Takahiko Iimura’s film Ai, as well as Yoji Kuri’s film Aos, and performed in works of Hi Red Center, among others.

Peggy Guggenheim, Yoko Ono and John Cage in Japan, 1962

Courtesy of Sogetsu Foundation, photo: Yasuhiro Yoshioka

Interpretations of Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit by Students of Jimmy Robert

7

Cut Piece

One of Ono’s most iconic and widely discussed performances, Cut Piece, emerged during this pivotal period in her career. First performed in 1964 as part of the Contemporary American Avant-Garde Music Concert: Insound and Instructure at the Yamaichi Hall in Kyoto, the work began with an invitation to the audience to come up one at a time on stage, cut away pieces of her clothing, and take it with them. Ono herself sat motionless and in silence on stage, a pair of scissors in front of her.

Ono herself performed Cut Piece several times, the latest iteration took place at Théâtre du Ranelagh, organised by the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, in 2003. Over time, the work has also been performed by a range of other people. In May 2025, the piece was performed by Berlin-based musician and artist Peaches in the atrium of Gropius Bau, as part of the exhibition YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND. This was not her first engagement with the work: in 2013, Peaches performed Cut Piece at the Meltdown Festival in London, at the personal invitation of Ono herself.

.jpg)

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1964, performed by Yoko Ono in New Works by Yoko Ono, Carnegie Recital Hall, New York, 1965

© Yoko Ono, photo: Minoru Niizuma

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece Performed by Peaches

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1964, performed by Peaches as part of YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND, Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2025

© Gropius Bau, photo: Holger Talinski

While Cut Piece is often interpreted through a feminist lens, the work invites multiple readings. One focus lies on the exploration of audience participation: by becoming performers themselves, the audience challenges the power dynamics between performer and spectator. Additionally, it is the performer’s stance – marked by stillness and surrender – that resonates with pacifist ideals. Ono made it clear from the beginning that Cut Piece could be performed by anyone, regardless of gender, and left it to the audience to choose how much they wished to take from the work, both materially and symbolically. Ono’s stillness on stage evokes the Buddhist concept of renunciation: the shedding of ego and the dissolution of fixed form.

“It was a form of giving, giving and taking. It was a kind of criticism against artists, who are always giving what they want to give. I wanted people to take whatever they wanted to, so it was very important to say you can cut wherever you want to.” — Yoko Ono, 1967

8

The Body as Battlefield

In 1964, Ono left Tokyo and returned to New York, where she quickly re-immersed herself in the city’s avant-garde and Fluxus circles. Alongside other artists, she staged numerous events, concerts and collaborative works, including The Stone at Judson Chuch, while also deliberately cultivating her own independent artistic trajectory. Her relationship with Fluxus, though close and creatively intertwined, remained marked by a certain ambivalence:

“Fluxus was George [Maciunas] and George was Fluxus. He would list all the names sometimes without the permission of the artists and then drop a name or two because he’d has a personal fight with them. He was headstrong and so was I.” — Yoko Ono, 1994

In 1966, Ono travelled to London to participate in the Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS) organised by critic Mario Amaya and artist Gustav Metzger. Bringing together artists, academics and activists, the symposium explored the role of destruction in art and society. Ono performed in two concerts at the Africa Centre that included a variety of pieces, including Cut Piece, Bag Piece, Strip-Tease For Three, Fly Piece among others, but Cut Piece attracted the most attention. She also performed Shadow Piece at the London Free School Playground and participated in symposia etc.

That same year, Ono’s first solo exhibition in London opened at the Indica Gallery. Unfinished Paintings & Objects by Yoko Ono showcased primarily white or transparent objects that were intentionally presented as “unfinished,” inviting viewers to complete them – either through interaction or imagination. The exhibition marked a moment in her career, not least because it was here that she met John Lennon, her future husband and long-time artistic collaborator.

Yoko Ono, Wrapping Piece, 1961, performed by Yoko Ono as part of Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Bluecoat, Liverpool, 26 September 1967

© Yoko Ono, photo: Sheridon Davies

9

A Feminist Avant-Garde Strategy

In response to the continued structural and cultural discrimination faced by women, the second wave of the feminist liberation movement emerged in the 1960s across the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and beyond. While the first wave had focused on securing legal rights and formal equality, the second wave broadened its scope to include issues such as sexual liberation, domestic and sexual violence, reproductive rights and workplace equality. While Cut Piece (1964) remains Ono’s most discussed work in feminist discourse today, it is several of her films that most directly engage with the core demands and themes of the feminist liberation movement of the time.

One such film, “RAPE”, was filmed in London together with Lennon in 1968. One of Ono’s most controversial works, the film tracks a woman as she is followed by a cameraman and sound person on the street to the cemetery, and ultimately to an apartment. Though she initially seems flattered by the attention, her growing discomfort becomes unmistakable. Palpably unsettling, the piece powerfully engages with themes of voyeurism, the film industry’s exploitative male gaze and the victimisation of women in society. At the same time, it reflects Ono and Lennon’s own situation in the spotlight, being hounded by the press, police and the public.

Yoko Ono, “RAPE”, film still, 1968/69, directed by Yoko Ono & John Lennon

© Yoko Ono

In another film, Freedom (1970), Ono spends a minute trying to free herself from her bra – an act that, though brief, directly challenges restrictive social norms. Both films exemplify her ongoing commitment to confronting taboos and advocating for gender equality.

Yoko Ono, Freedom, 1970, performed by Yoko Ono, directed by Yoko Ono, soundtrack by John Lennon

© Yoko Ono

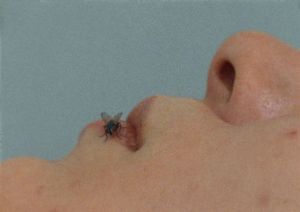

Ono’s interest in avant-garde film was shared by Lennon, with whom she collaborated on FLY in 1970. She wrote the script and also composed and performed the film’s music, which forms an integral part of the work. In the film, a fly moves continuously back and forth across a woman’s body. Often perceived as dirty or bothersome, the insect is impossible to ignore – it unsettles and persists, impossible to chase away. Here, it becomes a symbol of rebellion, liberation, and the disruption of societal expectations.

.jpg)

Yoko Ono, FLY, 1970/71, directed by Yoko Ono & John Lennon, score and concept by Yoko Ono, soundtrack by Yoko Ono & John Lennon

© Yoko Ono

Ono’s feminist strategies are embedded in her avant-garde approach. Not only in the 1960s, but also earlier in her youth and continuing to the present day, Ono’s critical interrogation of established ideas has consistently involved a refusal to accept prescribed gender roles. She has always used her voice to question the established order and expose injustice.

In 1972, Ono published the article “The Feminization of Society” in The New York Times. The piece called for solidarity among all women and a reorientation of society towards values associated with femininity. At the same time, it addressed the shortcomings of second-wave feminism, particularly its failure to represent all women, regardless of background, and its neglect of racism and intersectionality as central feminist concerns.

10

Activism: MESSAGE IS THE MEDIUM

Bottoms

Not long after her 1966 solo show at the Indica Gallery in London, Ono returned to a recent film project she’d begun in New York: Film No. 4 (Bottoms), included in George Maciunas’ Fluxfilm Anthology. The footage from New York featured a sequence of moving naked ‘bottoms’, including those of Philip Corner, Anthony Cox, Bici Hendricks, Geoffrey Hendricks, Kyoko Ono, Yoko Ono, Ben Patterson, Jeff Perkins, Carolee Schneemann, James Tenney, Pieter Vanderbeck and those of some other friends. Back in London, Ono placed a newspaper ad seeking “intellectual bottoms” to appear in an expanded version of the film. Over the course of ten days, more than 200 people participated before the camera. Conceived as a “petition for peace” the procession of butts offered an alternative to traditional political gestures. The accompanying score provided the following instruction: “String bottoms together in place of signatures for petition of peace.”

Initially censored, the film was only released in cinemas after high-profile protests led by Ono and her circle of friends. The controversy, along with widespread media coverage, brought Ono a surge in public attention.

Yoko Ono, FILM NO.4 ('BOTTOMS'), film still, 1966/67

© Yoko Ono

“I came from a tradition where if you do a work of yours on the stage and the audience – all of it – walks out on you, then it's a very successful concert, because that means that your work is so controversial, so far out that the audience could not accept it. If you did a piece that everybody could just enjoy and sit relaxed through until the end, then you were hitting the oldest chord in them. My work wasn't immediate, it didn't have a sense of immediacy in terms of popularity.” — Yoko Ono

WAR IS OVER!

IF YOU WANT IT

The enormous public interest in her relationship with Lennon, who was already a global celebrity, brought about a shift in Ono’s work. No longer addressing a relatively insular avant-garde community, she began to harness their media visibility to engage a mass audience, using their platform to communicate with millions.

Amid the social and political upheavals of the 1960s – Vietnam War protests, civil rights movements and feminist activism – Ono and Lennon launched a series of peace campaigns that relied on simple statements or texts and wide media reach. Among the most iconic were WAR IS OVER! IF YOU WANT IT and the Bed-ins for Peace (both 1969), in which the couple protested by remaining in bed for several days, surrounded by cameras and inspired by the tactics of civil rights sit-ins. Their message to the public was clear: change is possible – “if you want it.”

Ono’s engagement with social and political themes extended into her musical work. Building on her musical training and early experiments with composition, she began using her voice as an instrument in performance contexts as early as the 1950s. The years following the release of her first collaborative album with Lennon, Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins (1968), proved especially fertile musically. In 1971, the couple left London and returned to New York and did a retrospective titled This Is Not Here at the Everson Museum in Syracuse, her first museum show, which marked the beginning of a new chapter in Ono’s creative output.

Yoko Ono, Bed Peace, 1969, directed by Yoko Ono & John Lennon

© Yoko Ono

11

Presence vs. Absence

An Unsanctioned Exhibition at MoMA

In 1971, Ono placed an advertisement in New York’s The Village Voice inviting the public to an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The exhibition, Museum of Modern (F)art, was neither sanctioned nor curated by the museum. With this conceptual intervention, Ono challenged institutional authority and playfully subverted audience expectation. Many visitors, unaware of the ruse, followed the ad’s invitation and showed up at the MoMA, unknowingly participating in the work itself.

Billed by Ono as a “one-woman show”, the piece began at the entrance to the museum, where a man stood wearing a sandwich board. The sign informed visitors that Ono had released flies in “the exact center of the museum”; the audience was invited to track their path through the building and out into the city beyond. The sandwich board bore the following text:

“flies were put in a glass container the same volume as yoko’s body the same perfume as the one yoko uses was put in the glass container the container was then placed in the exact center of the museum the lid was opened the flies were released photographers who has been invited over from england specially for the task is now going around the city tosee how far the flies flew the flies are distinguishable by the odour which is equivalent to yokos join us in the search observation & flight12/71.”

Through her conceptual exhibition, Ono both challenged visitor expectations and commented on the institutional erasure of female artists. The empty glass container, left behind after the flies were released, became a symbol of absence – specifically, of the exclusion of women from museum collections. The deliberately vacant space, paired with the funny and provocative title Museum of Modern (F)art. one woman show and the use of insects generally considered a nuisance, drew attention to the injustice of an art world that, at the time, largely ignored women’s artistic work

More than 40 years later, in 2015, Yoko Ono had her first solo exhibition at MoMa, titled Yoko Ono: One Woman Show 1960-1971.

12

Music for Survival

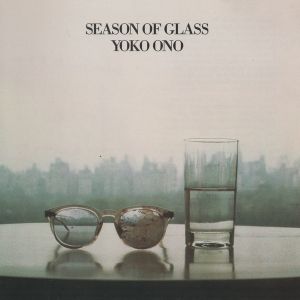

In August 1980, Ono and Lennon reunited in the studio to record Double Fantasy, their first album together in eight years. Released in November, the album went on to win the 1981 Grammy Award for Album of the Year – for John Lennon a posthumous recognition. Less than a month after the album release, on 8 December 1980, Lennon was assassinated outside their New York home, with Ono by his side. In the aftermath of his death, she turned increasingly to music, releasing several albums throughout the 1980s. As she would later recall, “It was music that made me survive.”

Five years later, in 1985, the Strawberry Fields memorial opened in New York's Central Park, a 10,000-square-meter landscaped area designed by architect Yoko Ono and Bruce Kelly in honour of her husband. In the years that followed, Ono remained politically active. In 1987, she travelled to Moscow to participate in an international forum dedicated to the anti-nuclear movement, continuing her longstanding commitment to peace and global activism.

Yoko Ono, Season of Glass, 1981, album cover

© Yoko Ono

In 1989, her solo exhibition Yoko Ono: Objects, Films opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibition signalled the art world’s renewed interest in Ono’s work, which can be observed internationally. Numerous solo exhibitions followed worldwide, such as Did you see the horizon lately? at Modern Art Oxford in 1997, YES YOKO ONO, organised by the Japan Society, New York, in 2000, Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, and YOKO ONO MORNING PEACE at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOT), Tokyo, both in 2015, YOKO ONO: MUSIC OF THE MIND at Tate Modern, London, and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, in 2024, as well as at Gropius Bau, Berlin, in 2025 and YOKO ONO: DREAM TOGETHER at Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin 2025.

Even now, at over 90 years old, Ono continues to engage audiences worldwide through her seemingly simple yet impactful works – brief instructions, participatory pieces and playful interventions that invite reflection and action. She has expanded the language of contemporary art while keeping key social issues, particularly peace, at the centre of her work. Her voice remains powerful and relevant, extending far beyond the boundaries of the art world.

Photo: Albert Watson © Yoko Ono

The Works of Yoko Ono at Gropius Bau

Contributors

Connor Monahan, Studio One

Jon Hendricks, Studio One

Jenna Krumminga, Translation

Patrizia Dander, Gropius Bau

Natalie Schütze, Gropius Bau

Vanessa Schaefer, Gropius Bau

Isabel Eberhardt, Gropius Bau

With special thanks to Connor Monahan, Jon Hendricks, Susie Lim and Studio One.

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)