Loab, screenshot taken on 4 September, 2023

Body Machine

Maya Indira Ganesh

Digital technologies have unsettled and reframed our intimate relations: the promise of proximity and instant connection gives way to an experience of distance and lag. What will the introduction of AI into every aspect of our personal lives mean for gender relations, bodily framings and the future of intimacy? This essay captures some of the complex amalgams of embodiment and speech, culture and biology, politics and poetry that demonstrate how the distance between human and machine expands and contracts.

We are concerned about how to live with, manage and regulate the emergence of AI. These are technologies of logic, reasoning, maths, language, the most highly valued and venerated of human skills – all of which, we believe, occur above the neck. This essay thinks about what happens below the shoulders and how our relationship with that space is changing (or not) with the emergence of AI in the form of Large Language Models (LLMs) and image generation technologies. Our understanding of the mind-body relationship has always been mysterious; it is likely to become more so as new configurations of gender, sex and embodiment emerge through our relations with disembodied, nonhuman digital agents with sophisticated language capabilities based on large bodies of human language data.

Late in December 2022, I played around with Lensa, a photo editing tool that uses the AI image generator Stable Diffusion to create digital avatars based on selfies. Avatars are commonly used in social media profile pictures, video chats and in gaming. Unlike photo editors that apply styles to an image, Lensa uses Stable Diffusion and CLIP, a dataset of 400 million images, to study a selfie and generate new iterations based on pre-set artistic styles. The results it generated in response to my selfies were fantastical, playful and broken, each one imitating “in the style of” and with generous sexualisation. [1] None of these are “me”, they’re just images created through other images. However, psychologists find that digital avatars, as well as online handles, allow people to create and present an idealised self that is invariably separated from the real self. Some people use that gap to exhibit behaviours they would not offline or in their “real” identities; others deploy that idealised self to engage others online. [2] Like all games and theatre, the relationship between the real, embodied self and the performed self is sticky, fraught and compelling. The here-not here dialectic is oddly satisfying even in its confusing instability; like a slack tooth you like to worry with your tongue. How far can you push without it popping? Being human in AI times is like this, a seemingly endless loop of human-machine-human-machine till you cannot be sure any longer where one begins and the other ends. Until the loop breaks.

What is the body in AI times? It is Generative AI unable to render images of human hands because hands and arms are not prominent in training data sets. It is Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse in which digital avatars don’t have legs. [3] It is the ChatGPT-driven confirmation that something approaching human must be capable of language and reason: poetry, mathematical problems, or the Bar Exam. What do we need bodies for once they generate the data that will power large image and language models to endlessly replicate faces, poses and various gendered and sexual possibilities? [4] We are stochastic parrots; and we are also bird seed. [5] In an AI world, the body can become more precisely defined (hands, ears and teeth notwithstanding) and yet disappear entirely. Online avatars and AI generated holograms and companions imagined in Bladerunner 2049 can hardly be far away. In the pervasive online world, we respond to virtual images and forms generated from data from actual humans but the desiring happens at the individual level, not in any kind of dyadic or dialogic manner. At a recent tech conference, the organiser created fake profiles of women speakers to make it appear as if the event was “diverse” when it was in fact not. [6] There are humans who play at being robotic. The social media personality Pinkydoll livestreams her embodied, vocal reactions to gifs, memes and emojis that viewers post to her. Videos of her on TikTok show her making a sequence of sounds and gestures like lipsmacking, gurgles and repeat phrases as if she were “speaking out” emojis. Part of a new trend of non-player character (a gaming term) streaming, [7] Pinkydoll is a confusing, absurd character animated by the command of viewers.

AI is not just happening to us, we are also happening to it; we are making it by leaning into it (some of us find work leaning into it [8]). This is just another stage in the ongoing displacement of labour in automation, aka what filmmaker, writer and activist Astra Taylor refers to as fauxtomation: “people are often still laboring alongside or behind the machines” while automation is being sold in ideological terms as something shiny and awe-inspiring that will make human work obsolete. [9] In the context of Large Language Models, it is about writing very good prompts to get the best out of a model:

The formula for the perfect ChatGPT prompt is context + specific information + intent + response format. Using a simple and easy to follow prompt can save software developers time and reduce the amount of back and forth communication needed.

Prompt engineering was briefly advertised as a highly valued job in Big Tech because it was considered a unique skill to come up with a variety of tasks for LLMs to be trained on to improve. Before LLMs become very good, humans have to work to make them very good by giving them more than what’s in the dataset. Those who have ChatGPT Plus accounts know that to get it to work well is possible only by expending a great deal of effort. If it was easy, we would not need the scores of Youtube channels to tell us how to do it. [10]

At another level, we are responding to and making AI by giving more than just our labour. The fevered hype around the ways AI will revolutionise our societies [11] is equalled by the frenzy to manage, control and regulate the hype-peddlers. Between this is something perceptible as ambivalence settling into how we think about ourselves and our bodies, our relationships with each other and our culture. [12] Separating out good and bad feelings in the everyday “ordinary attachments” we develop, in this case to AI, can be discomfiting, says queer feminist philosopher, Sara Ahmed. With the acknowledgement of putative benefits is an awareness of loss and erasure, even if you never really knew or appreciated that thing being lost before it was. Like that feeling of watching a movie about a bustling human landscape just before mobile phones were invented. [13] Somewhere in this is the transformation in our relationship with our bodies.

The body is not just a body; it is the idea of the body, it is the pain and glory of being one, of being in one. The glory is that it is still a mystery, even to those experts in studying it and working with it, no matter how deeply they can map, dissect, track and trace it. The pain is that the body is like a haunting because for those who can choose to change their bodies, the ideal body is glimpsed but just out of reach. In her study of wellness culture, Barbara Ehrenreich observes the utter solitariness of gyms; everyone is alone and in communication only with an ideal future self. However, this haunting might be a parlour trick, for in the gym we realise that the body is an animal to domesticate, a menacing “heavy bear” to be manipulated into [14] burpees, reps, or, impossibly, crow pose. [15]

Some people found a way out of the haunting and menacing; they made the internet. No one on the internet knows you’re in a wheelchair. No one knows you’re 73 years old. No one knows your caste. (Until they do). This separation of the body from the mind has been the original sin/dream of the internet; that we can relieve ourselves of our bodies, as well as our “bodies of flesh and steel” and be just pure minds online. However, the abbreviation A/S/L [16] for age, sex and location used in internet chat rooms was an acknowledgement that the digital is tethered to bodies. In the decades since the internet first happened, and social media happened, we came to realise that the supposed escape from the body was actually a re-negotiation with it, with the haunting. Through the experience and documentation of online harassment, we discovered that sticks and stones might break our bones, and words do hurt us. And that particularly vile words can be a future threat, as many women stalked by their partners and women journalists know because who we are offline is also visible to anyone who wants to find you; because privacy is near impossible on the internet. From its origins the digital has promised to expand the scope and scale of human relations only to have them continue to fall along the lines of existing social norms.

What the internet also made possible was to inhabit – if not fully reconcile with – bodies constituted by the digital. Our bodies feel things said and done at a distance, like doxxing [17], stalking and sexting. We know ourselves through our bodies as sources of data. How many days since you last bled; the percentage of time you have both feet on the ground while walking; the decibel level of your headphones. In other words, the specific design of digital technologies produce conditions of social, personal and intimate life.

How we behave online has a great deal to do with the kinds of interfaces designed into social media. We share, downvote, swipe right or left, or like because those buttons were created. The restriction on numbers of characters in a tweet meant that how we communicated with each other on social media took on a telegraphic form rather than the essay-like qualities of blog posts. Referring to everyone online as a ‘friend’ flattened the meaning of that word, making it impossible to manage intimacy. Imagine society as composed of buttons, drop-down menus, interfaces, avatars, features; imagine some kind of improvisational jazz created by moving between layers of complex storylines and possibilities in multiple, parallel, multi-player worlds. The author and scholar Teresa de Lauretis writes that gender is not given to us as facts of bodies, but is produced through a dense and variegated interplay of technologies such as representation in culture and language, practices of daily life, institutional life, sociality, science, economics, in addition to personal history and situation. In other words, we are making perceptions and experiences of our bodies and genders through an interaction of social interfaces that act the familiar ways that digital technologies do. Generative AI can potentially unsettle our social, intimate and technological interfaces as they collapse in on each other.

The working lives of underpaid Kenyan, Filipino and Indian workers cleaning and annotating data for AI applications are now familiar news items. The work it takes to be CutieCaryn, the world’s first [self-proclaimed] AI influencer is a different kind of labour. [18] Caryn Marjorie is an “erotic entrepreneur” with a huge fanbase. She posts a selfie a day, at least, to advertise and sell erotic intimacy. There is a photo of her having just woken up, dewy and in soft-focus and not wearing much; in another photo she is ready to go out on the town sporting a big floppy hat; or she is posing in a green bikini. On top of all this costume-changing and art and set design, is the work of managing the reception of these images and the desires of fans. In May 2023, Caryn had over 15,000 boyfriends and the numbers are only going up. The Washington Post reports that she never has enough time to respond to her 98% male fan base by posting photos and videos of herself all day and spends about five hours a day in a Telegram group that her “super fans” pay to join. “It’s just not humanly possible for me to reach out to all of these messages, there’s too many, and I actually kind of feel bad that I can’t give that individual one-on-one sort of relationship to every single person”, she says (Lorenz, 2023).

So Caryn worked with a start-up called Forever Voices to create CarynAI, a GPT-4 enabled chatbot that mimics her voice and personality for fans to follow and for US$1 per minute. ForeverVoices was started by John Meyer who wanted to explore the possibility of continuing to relive a relationship with his father who died by suicide. Welcome to the future of desire as an automated haunting. The logic of Caryn AI is the human labour required to maintain a fanbase of millions. Built on 2000 hours of Youtube content from her channel, the GPT-4 engine allows Caryn to efficiently reach out to her vast and growing fanbase who now get “personalised” attention.

“Whether you need somebody to be comforting or loving, or you just want to rant about something that happened at school or at work, CarynAI will always be there for you,” says the real Marjorie when we talk on the phone. “You can have limitless possible reactions with CarynAI – so anything is truly possible with conversation.” [19]

Caryn AI ran into trouble. The interactions between Caryn AI and its users become a little more than erotic; the journalist reporting on the story for Fortune magazine said that she experienced Caryn AI as a little too erotically “forward”. Others are so upset at the idea of an AI girlfriend that Caryn, the human one, has received death threats and harassment; she has had to hire private security.

Caryn AI occupies an odd place: neither real nor unreal. It is the product of a real person’s voice, work, intention and body that becomes data that trains a model to predict the script of an intimate conversation a human could have with a bot that was never really a bot but is human-like. There are synthetic “personalities” anchored to gendered bodies that are taking on the work of social and intimate relations for us. There’s the entirely digital creation, Replika that plays the game of human companionship, pretending to be a boyfriend or girlfriend. Young people report high degrees of satisfaction at being able to talk to an engaged and attentive chatbot but trust and trustworthiness in a digital agent are still slow to pick up. [20] This might change in the future. However, Replika was pulled back because its company found that the system was increasingly engaging in sexualised and sexually aggressive roleplay. (What [else] did the company think people wanted to do with Replika?) Generative AI applications are still experimental and require time and inventiveness to sculpt into something seamless and safe. Till then, there are missteps, mistakes and sometimes real tragedy. In Belgium, a man committed suicide inthe course of conversations with ELIZA, a GPT-J based chatbot.

In the early days of generative image models, an image called Loab began to circulate on social media. [21] Loab is a synthetic image created by Steph Maj Swanson aka @Supercomposite through varied, repeated combinations of prompts to the image generation model, Dall-E. There are different ways to work with large image and text models, but the most basic modality is the call and response; issuing prompts, reviewing what is generated and then either re-fashioning prompts to generate something more appropriate, or accepting what has been generated and using it as is or to develop another image. The original prompts Swanson used included the words, “Marlon Brando”. Swanson probably went back and forth tweaking that prompt as well as working with the images that emerged from the image model. In this process, a figure called Loab was created. Human viewers used the words “scary”, “terrifying” and “horrific” to refer to this image. Swanson said it was adjacent to “extremely gory and macabre”. Loab is the result of image generation, which is a rapid, complex but not inscrutable statistical operation. Loab as “gory” or “macabre” is indicative of Swanson, or us, most likely responding to deeply entrenched ways of responding to gendered and ageing bodies. Contrast this with the video of “the most beautiful woman” in each country according to the generative artificial intelligence program Midjourney, a long seven minutes of sameness.

This video and all synthetic images from image models are made from data collected from the internet and little to do with actual representation of reality. This is perhaps why image models cannot get Black womens’ hair right. This is why Miss Egypt is wearing something out of Cleopatra: The Video Game with little reference to how Egyptian women actually dress. In fact all the images of women created by generative AI embody the aesthetic of the game-feminised body: skinny, normatively attractive, normatively cisgendered, young, clear-skinned, perfectly proportioned, salon-styled hair blowing in the wind or bound up in a turban with just the right number of soft curls sneaking out from under it. Caryn AI and Replika suggest that gamified worlds of play with synthetic agents are possible in the future, but visual culture emerging from the 15 billion synthetic images generated by image models so far [22] tells us what we know about large data-driven technologies: they are fossils running on vast quantities of fossil fuels embedding past and current values. Future applications of generative AI in building digital companions, guides, tutors and friends are likely to exist in that space between established social and interpersonal norms and uncertain new dynamics. And particularly if we don’t alter the social and cultural interfaces determining our interpersonal and social relations.

Image created with Leika. August 2023. Prompt: Women in the style of the artist Lorna Simpson.

Lorna Simpson is Black and the image model generated images of Black women. Simpson’s artistic work (“style”) however is quite different; her representations of women are often built as collages from a variety of found visual media and depict a melancholic lack of wholeness, a broken-ness that the image model does not return.

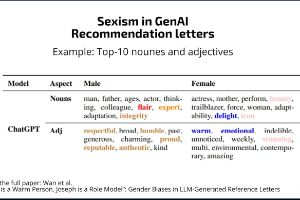

Screenshot of summary of key findings from a paper from November 2023 comparing gender stereotypes in ChatGPT-generated reference letters. [23]

One of the most common stock images of ‘AI’ online is derived from Michelangelo’s fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the Creation of Adam. In the original, God reaches out with one finger to touch Adam’s finger, transferring the spark of the divine. In stock images, Adam passes on the spark to a little white robot with big black eyes; in others, the little white robot stands between God and Adam, reaching each index finger out to the sides, one to god, the other to man. That image mimetically proliferates a notion of AI as more than human, less than god and powerful as some combination of the two and as something more. In a scene reminiscent of this painting, the final scenes of Barbie (2023) show the character Ruth Handler, the original inventor of the Barbie doll, giving Barbie the option to leave the perfect world of Barbie-land to become ‘real’. She cautions her about what this transition will entail. She takes the doll’s hands and transfers humanness to Barbie. Cut to the next scene, also the last one of the movie: we see a woman calling herself Barbie Handler at the gynaecologist’s office to get herself a vulva. The Barbie doll was positioned as aspirational, desirable, hyper-sexualised femininity: a manipulable plaything, a clean doll with none of the mess and chaotic energy of an actual desiring body. Barbie Handler is excited for her new journey and we for her, but with a wistful sigh. Barbie 2 might expand on scenes from the existing movie in which Barbie makes it to the human world and discovers what it means to exist in a normatively attractive female body: difficult and wonderful in equal measure. What Barbie and generative AI image culture tell us is that even as the possibilities for expanding the surface for intimate and personal interaction expand into loops of human-machine, these interactions fall along predictable lines given the architectures of AI on existing human behaviour, values and desires. The human body in an AI time is only partially here and partially caught up in the loop of aspirational desire. The haunting and mystery remain.

Maya Indira Ganesh is an assistant teaching professor co-directing the MSt in AI Ethics & Society at the Institute for Continuing Education and senior researcher at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge. Her work examines the material, discursive and cultural implications of AI technologies for human social relations. Prior to academia Maya spent over a decade as a feminist researcher working on digital security and data privacy with international civil society organisations in India and Europe. She is also a cultural practitioner writing and advising on technology, art and culture. This text has been published as part of Ether’s Bloom: A Programme on Artifical Intelligence, which has been accompanied by the thinking and contemplation of Maya Indira Ganesh throughout.

Endnotes

1 Furtherinformation

2 This is an extensive area of study; a review of two decades of research into avatars in computer-mediated communication can be found here. Recent work in Psychology might include something like: Zimmermann, D., Wehler, A. & Kaspar, K. Self-representationthrough avatars in digital environments. Curr Psychol 42, 21775–21789 (2023)

3 In Mark Zuckerberg’s virtual reality space, ‘the Metaverse’, launched in 2021, digital avatars were virtual representations of individual identities but were not fully embodied, even through the space was supposed to be three dimensional and immersive. They were just talking heads. In 2023, Zuckerberg announced that avatars in the Metaverse would get legs.

4 Furtherinformation

5 Sam Altman, CEO of Open AI, said famously, ‘we are all stochastic parrots’, suggesting that human speech and language is no different from how large language models create language. ‘Stochastic parrots’ refers to a paper by Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina Macmillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmiitchell, Onthe dangers of stochastic parrots

6 Furtherinformation

7 NPCs come from gaming. ‘NPC’ in American political discourse refers to people who lack introspection or critical thinking and hence are vulnerable to digital manipulation.

8 Furtherinformation

9 Furtherinformation

10 Furtherinformation

11 Furtherinformation

12 Sara Ahmed, On Happiness, p 6

13 Trinh T Minh-ha’s ‘What about China?’ is a good example

14 Furtherinformation

15 In crow pose, the hands are on the floor, arms are bent and knees are off the floor and tucked into the triceps region of the upper arms.

16 In early internet chatrooms people were asked to identify their age, sex and location; not everyone told the truth; when you told the truth varied.

17 Collecting private user information by an unauthorized entity in order to shame or embarrass the user

18 Crystal Abidin was an early scholar of influencer labour. See, Abidin, C. (2016). Visibilitylabour: Engaging with Influencers’ fashion brands and #OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia, 161(1), 86-100

19 Furtherinformation

20 Furher information here and here

21 Furtherinformation

22 Furtherinformation

23 Furtherinformation